Our health care system has been designed to meet the needs of those providing the services. While this may work for some Canadians, it comes up short for marginalized communities who encounter complex barriers accessing health care.

Barriers may include lack of transportation, financial means, lack of identification or permanent address, poor past experiences with the health care system and many others. Take a moment and think about your last experience at your doctor’s office or emergency room. Was it trauma-informed?

The consequences of inaccessible health care are considerable, both on an individual and systemic level. People may delay getting medical help, which often leads to worsened health outcomes. The need for emergency services may increase, which is more expensive to the system than prevention, early detection and treatment.

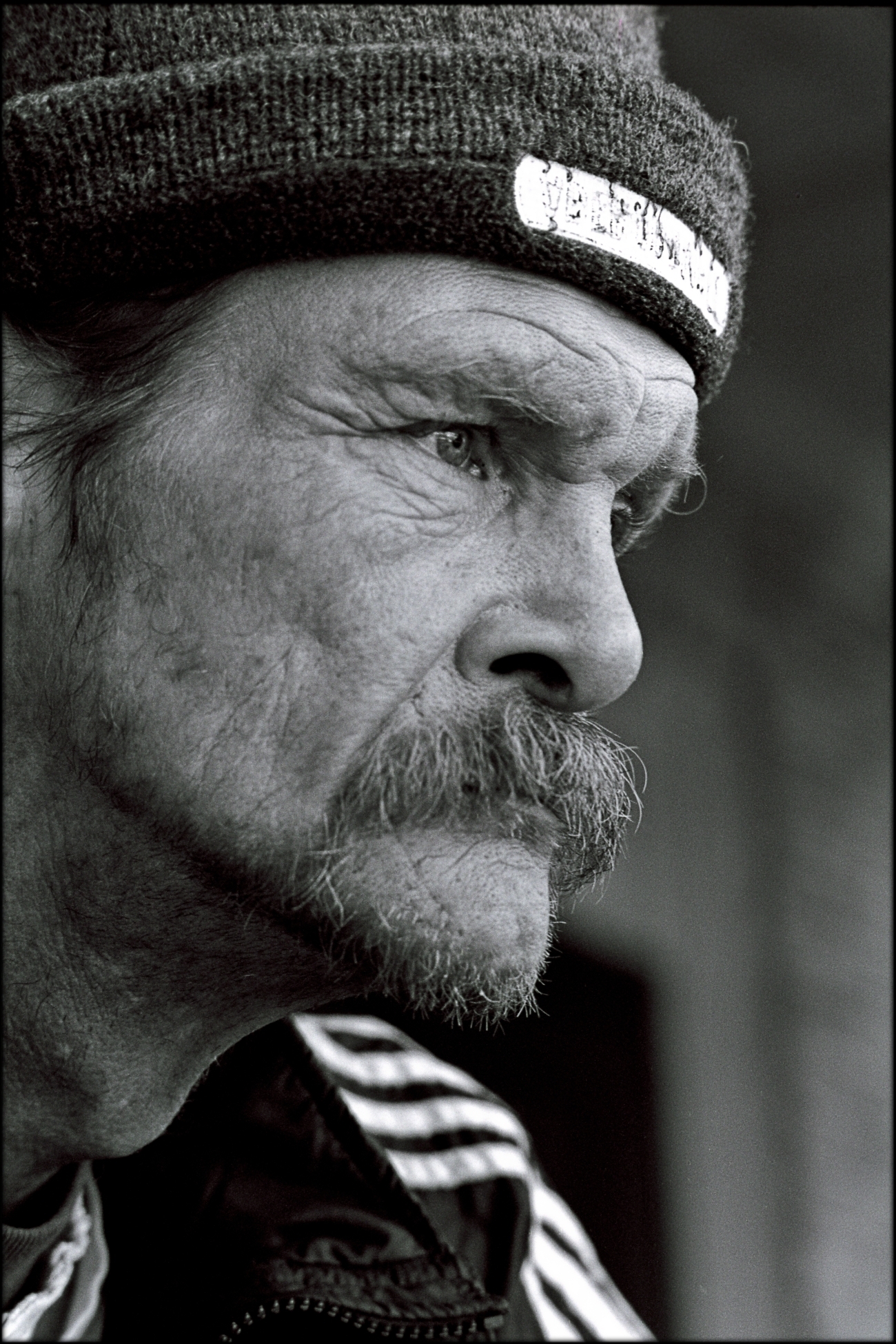

Adam’s Story

Adam is a 47-year-old who has experienced chronic homelessness for 20 years. He walks about 5 kilometers a day carrying his belongings seeking shelter and warmth in Calgary’s downtown core.

He started noticing swelling in his legs and fatigue that was out of the ordinary. As time went by, he started noticing his urine was darker than normal, and the whites of his eyes had a yellow tint to them. That’s when Adam knew something wasn’t right.

He’s had bad experiences in medical settings though – most recently when he visited an emergency room for frost-bite. Adam lives on the street and when it’s extremely cold outside he drinks alcohol to feel warm. That day he drank a bottle to numb the cold but started noticing discoloration in his hands. He walked to the nearest hospital while Calgary was experiencing a 40 below cold snap. Noticing he was intoxicated, the staff were short and impatient with Adam. He felt very judged, and the clinical setting reminded him of the trauma he experienced while being hospitalized for mental health problems in the 1980s. He promised himself he would never return.

Now, years later, Adam knows he needs to see a doctor about his symptoms but doesn’t want to relive that experience. Because he’s experiencing homelessness, Adam is focused on daily survival, working hard to find food and shelter. He just doesn’t have the time or energy to think about worsening symptoms. He hopes they’ll go away on their own.

Adam was suffering from a Hepatitis C infection, which was slowly causing chronic liver disease. Treatment of Hepatitis C is very effective when caught early. If Adam had access to compassionate, non-judgmental care, the rest of his life would’ve been different. He could’ve avoided cirrhosis, kidney damage, and heart problems, and he may not have been ambulanced to an emergency room with liver failure years later.

How we work towards “zero-barrier” care

At The Alex, we believe that all community members, regardless of their situation, deserve accessible health care. That said, providing care that truly has zero barriers while operating within the healthcare system may always be an aspirational goal. It is imperative that we regularly review our processes to identify barriers our programs may be posing for community members.

Whether that’s ensuring our spaces are dignified and comfortable, training all our staff in trauma-informed care, or physicially bringing our services to those who need it, we strive to ensure that coming to The Alex is the first step towards wellness.

At The Alex, we do this by providing:

- A peer-led Street Team that provides substance use and mental health support to those experiencing homelessness across the city.

- A fleet of four mobile health buses that act as clinics-on-wheels visiting identified high-needs locations and schools around Calgary to provide physical health, mental health, and dental care.

- Walk-in hours and phone intakes.

- Temporary housing for people experiencing homelessness during the pandemic.

- Home visits by a team of case managers and specialists.

- A Rapid Access Addiction Medicine clinic which ensures that when a person makes the decision to address their addiction, immediate, unbiased, and stigma-free support is available and the “window of opportunity” is not missed.

- A large Housing First program that does not require sobriety or other conditions to being housed.

As a not-for-profit with about 400 staff serving over 10,000 people each year, we have the scale but also the flexibility to offer health care in novel ways.

But we are only one organization, in one city in Canada. System-wide changes are overdue, which is why we advocate with the Canadian Association of Community Health Centres (CACHC) and every level of government for this model to be more widely adopted. When we make health care more accessible, more Canadians can access care that truly meets their needs.