I think the first time it hit me that life had radically changed was when I took my wedding band off permanently. The cherished piece of jewelry that my husband gave me had belonged to my husband’s grandmother and was really important to me. But it had many crevices that could harbour harmful germs, including the Coronavirus.

The first time I set foot into the somewhat dated hotel in the north-east of Calgary that served as the Assisted Self-Isolation Site (ASIS) I thought I would spend a few weeks in the empty ballroom where we all sat on plastic chairs and folding tables. Working at ASIS seemed dreamlike, even magical. Time didn’t exist – 11, 12 or even 13 hours felt like the blink of an eye. We called it the ASIS ‘time warp’. The workload was immense and the energy in the building was frenetic but it was also euphoric and maybe even a little addictive.

I felt a full range of emotions every day: fear, joy, belonging, connection. Things formerly important to me became a faint afterthought – who pays attention to color-coordinated clothing and make-up during a pandemic?! Things I had never thought about before became all-consuming, like how to get rid of the rash the mask is causing. My life turned into a cycle of sleep-work-eat and little else. My ever-supportive husband had meals on the table and my laundry washed and ready to go, allowing me to conserve any extra energy I didn’t have anyways.

Working at ASIS seemed dreamlike, even magical. Time didn’t exist – 11, 12 or even 13 hours felt like the blink of an eye. We called it the ASIS ‘time warp’.

I distinctively remember a pivotal moment during my time at ASIS. It was the visceral anxiety I felt when I heard that the first COVID-19 cases had popped up at the largest homeless shelter. The day (a Sunday) was spent in meetings trying to figure out what this meant. It was estimated that potentially 800 clients had been exposed. Since we had moved so quickly to pull the program together, a million thoughts crossed my mind: Do we have enough staff? (No). Are all policies and procedures in place? (No). Do we have enough mental health support? (Also, no).

I talked to my elderly parents frequently during this time. They live in Germany, dangerously close to northern Italy where hospitals ran out of room in the morgue and (often unidentified) bodies were taken to ice rinks to keep cool. Healthcare providers over there were likening their experience to working in combat zones. I had visions of ASIS clients passing away. I racked my brain to come up with a plan how to protect staff but also how to accept a large amount of clients in a very short period of time. But then test results started coming back and they were negative. More came back; all negative. The few clients that came to ASIS who were COVID positive were not that sick. Many were completely asymptomatic.

We knew we could do what had seemed impossible. We had figured out how to provide good care to vulnerably housed individuals…

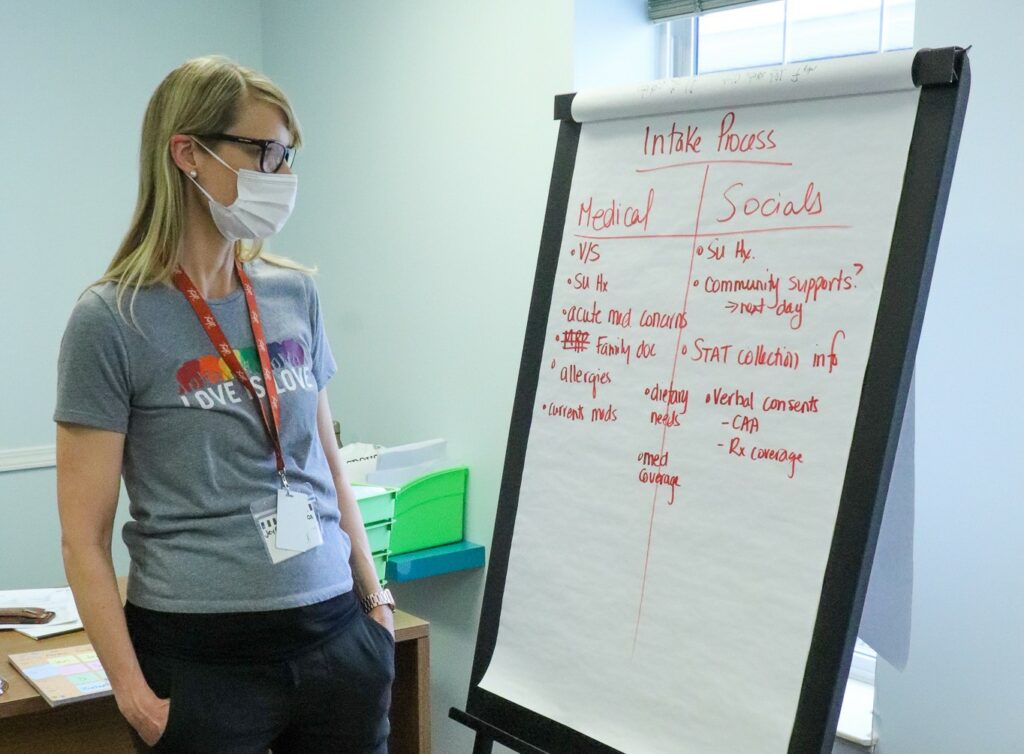

In the meantime the team pulled together and did the work that needed to be done: hiring staff, developing protocols and procedures, working out kinks in the process with transportation, medication management, dealing with clients eloping and supporting the needs of the ones using substances.

There was a second turning point. After a few incredibly busy days in which we were admitting up to 14 clients in a day, all of a sudden there was a calm to our operation that was palpable. The frantic, anxious energy had dissipated and there seemed to be a confidence to our work. We knew we could do what had seemed impossible. We had figured out how to provide good care to vulnerably housed individuals who are accustomed to congregate living, and spending time with their street family while dealing with mental health and addiction issues, boredom, and trauma.